Primary Key Tables: Unifying Log and Cache for 🚀 Streaming

Modern data platforms have traditionally relied on two foundational components: a log for durable, ordered event storage and a cache for low-latency access. Common architectures include combinations such as Kafka with Redis, or Debezium feeding changes into a key-value store. While these patterns underpin a significant portion of production infrastructure, they also introduce complexity, fragility, and operational overhead.

Apache Fluss (Incubating) addresses this challenge with an elegant solution: Primary Key Tables (PK Tables). These persistent state tables provide the same semantics as running both a log and a cache, without needing two separate systems. Every write produces a durable log entry and an immediately consistent key-value update. Snapshots and log replay guarantee deterministic recovery, while clients benefit from the simplicity of interacting with one system for reads, writes, and queries.

In this post, we will explore how Fluss PK Tables work, why unifying log and cache into a persistent design is a critical advancement, and how this model resolves long-standing challenges of maintaining consistency across multiple systems.

🚧 The Log-Cache Separation

Before diving into how Fluss works, it’s worth pausing on the traditional architecture: a log (like Kafka) paired with a cache (like Redis or Memcached). This pattern has been incredibly successful, but anyone who has operated it in production knows the headaches.

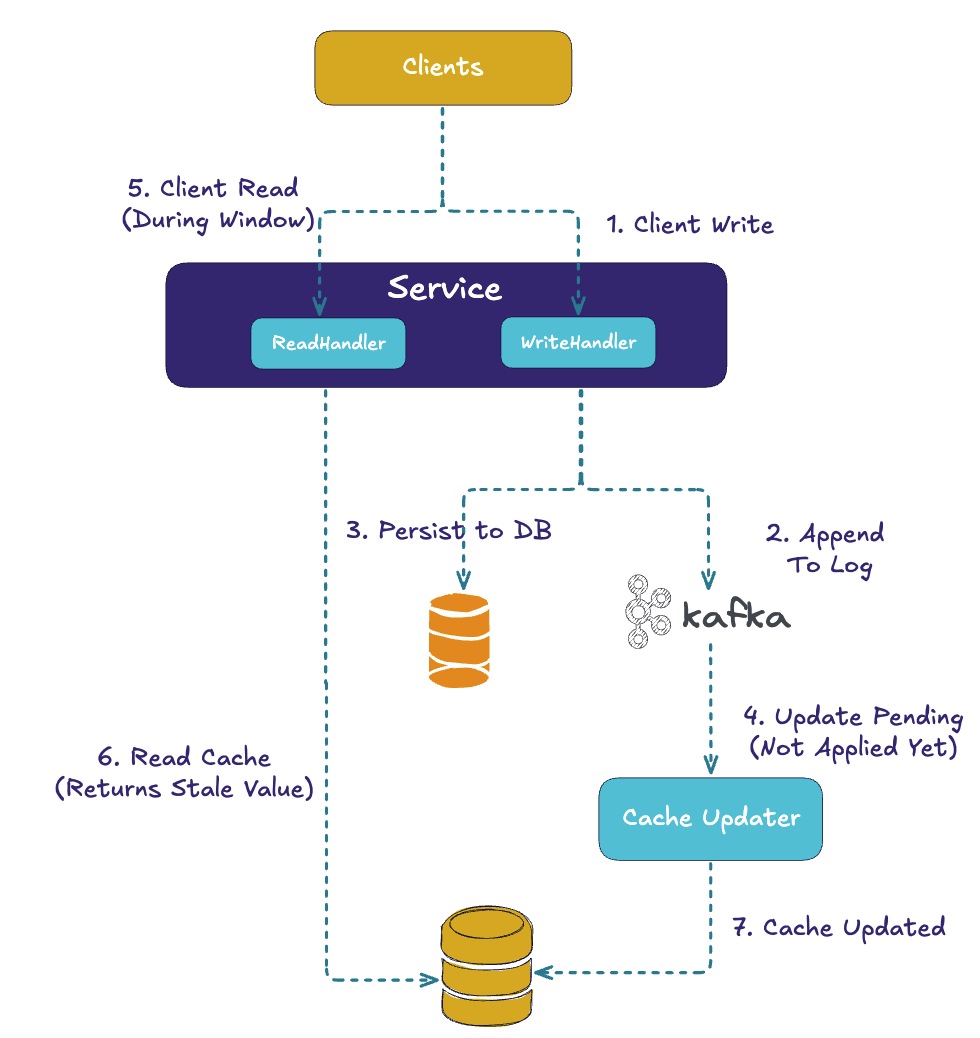

The biggest challenge is cache invalidation. Writes usually flow to the database or log first, and then the cache has to be updated or invalidated. In practice, this often creates timing windows: the log might show an update that the cache hasn’t yet applied, or the cache may return stale data long after it should have expired. Teams fight this with TTLs, background refresh daemons, or CDC-based updaters, but no solution is perfect. Staleness is a fact of life.

Another pain point is dual writes and atomicity. Applications frequently need to update both the log and the cache (or log and DB, then cache). Without careful orchestration, often using an outbox pattern or distributed transactions, it’s easy to end up with mismatches. For example, the cache may be updated with a value that never made it into the log, or vice versa. This not only creates correctness issues but also makes recovery from failure very hard.

Operationally, running two systems is simply heavier. You need to deploy, monitor, scale, and secure both the log and the cache. Each comes with its own tuning knobs, resource usage patterns, and failure modes. When things go wrong, debugging is often about figuring out which system is “telling the truth.”

Finally, failover and recovery are fragile in a dual-system world. If the cache cluster restarts, you might start from empty and experience surges as clients repopulate hot keys. If the log has advanced while the cache is empty, reconciling the two can be messy. The promise of “fast reads and durable history” often comes with the hidden cost of reconciliation and re-warming.

This is the context Fluss was designed for. The goal is not to reinvent the wheel but to unify the log and the cache into one coherent system where writes, reads, and recovery all flow through the same consistent pipeline.

TL/DR

The Key-Value (KV) store forms the foundation of the Primary Key (PK) tables in Apache Fluss. Each KVTablet (representing a table bucket or partition), combines a RocksDB instance with an in-memory pre-write buffer. Leaders merge incoming upserts and deletes into the latest value, then construct CDC/WAL batches (typically in Apache Arrow format) and append them to the log tablet. Only after this step is the buffered KV state flushed into RocksDB, ensuring strict read-after-log correctness.

Snapshots are created incrementally from RocksDB and uploaded to remote storage, enabling efficient state recovery and durability.

Inside Fluss PK Tables

🔑 Fluss PK Tables: The Unified Model

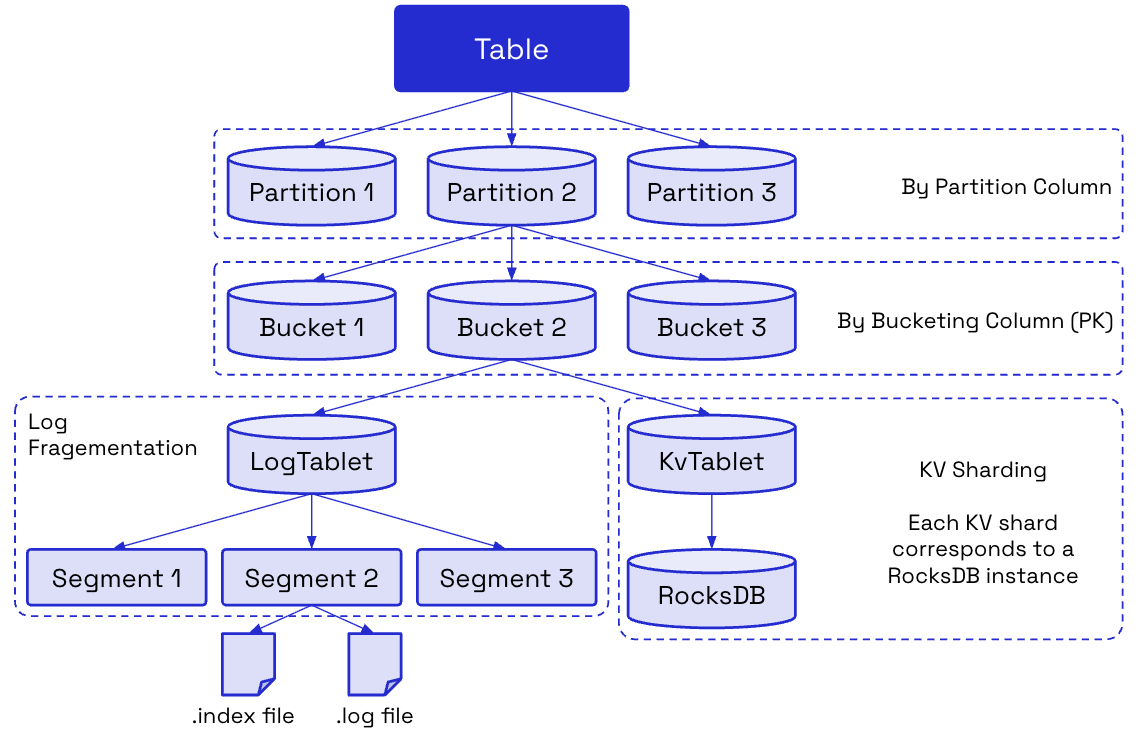

In Fluss, a Primary Key Table consists of several tightly integrated components:

- KvTablet: in the Tablet Server stages and merges writes, appends to the log, and flushes to RocksDB.

- PreWriteBuffer: is an in-memory staging area that ensures writes line up with their log offsets.

- LogTablet: is the append-only changelog, feeding downstream consumers and acting as the durable history.

- RocksDB: is the embedded key-value store that acts as the cache, always kept consistent with the log.

- Snapshot Manager and Uploader: periodically capture RocksDB state and upload it to remote object storage like S3 or HDFS.

- Coordinator: tracks metadata such as which snapshot belongs to which offset.

Together, these components give Fluss the power of a log and a cache without the pain of reconciling them.

✍️ The Write Path

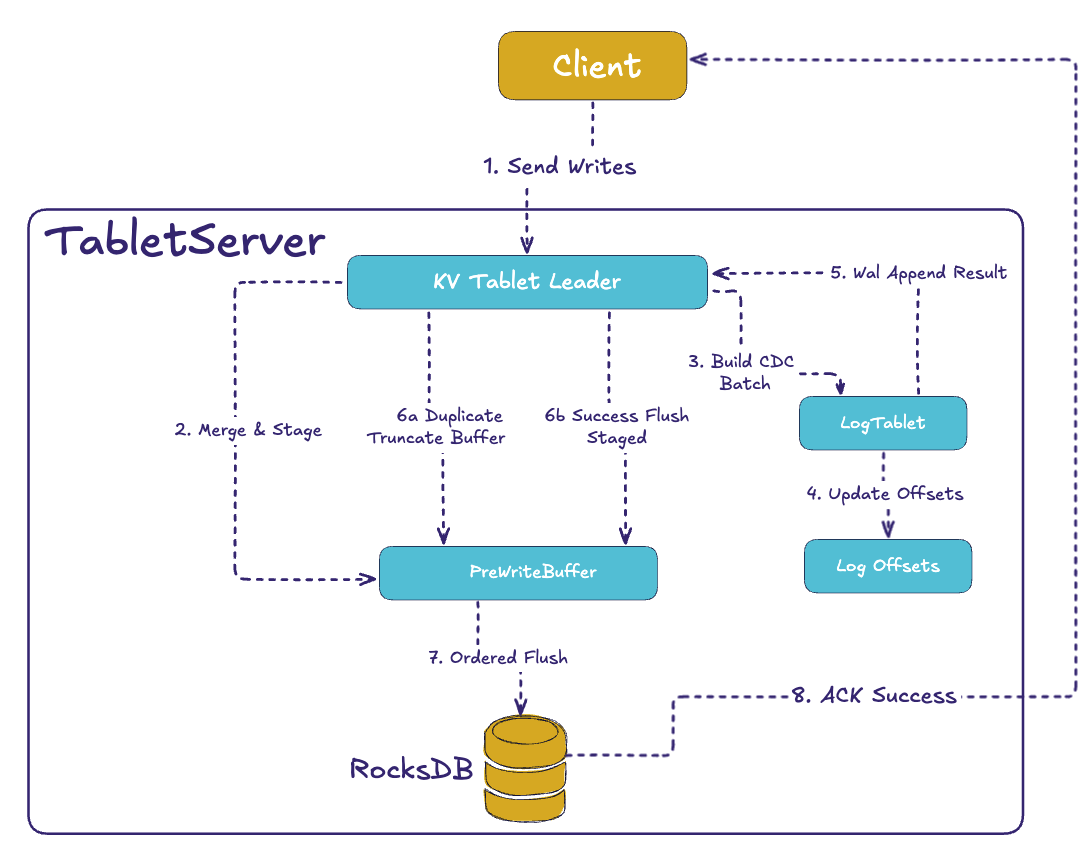

The write path is where Fluss’s guarantees come from. The ordering is strict: append to the log first, flush to RocksDB second, and acknowledge the client last. This removes the classic inconsistency where the log shows a change but the cache doesn’t.

Here’s how the flow looks across the key components:

When a client writes to a KV table, the request first lands in the KvTablet. Each record is merged with any existing value (using a RowMerger so Fluss can support last-write-wins or partial updates). At the same time, a CDC event is created and added to the log tablet, ensuring downstream consumers always see ordered updates.

But before these changes are visible, they’re staged in a pre-write buffer. This buffer keeps operations aligned with their intended log offsets. Once the WAL append succeeds (including replication), the buffer is flushed into RocksDB. This order – WAL first, KV flush after – guarantees that if you see a change in the log, you can also read it back from the table. That’s what makes lookup joins, caches, and CDC so reliable.

Note: One important detail is that log visibility is controlled by a log high-watermark offset. The KV flush operation and the updates to this high-watermark are performed under a lock. Since the log and KV data of same bucket, reside in the same process, we can use a local lock to synchronize these operations, avoiding the complexity of distributed transactions.

So it's not only about "if you see a change in the log, you can also read it back from the table", but also "if you see a record in the table, you can also see the change from the log".

Idempotent writes: ensure a message is written exactly once to a Fluss table, without any out of orderness. Even in scenarios that the producer retries sending the same message due to network problem or server failures.

In a nutshell: Every write flows through a single path, producing both a log event and a cache update. Because acknowledgment comes only after RocksDB is durable, clients are guaranteed read-your-write consistency.

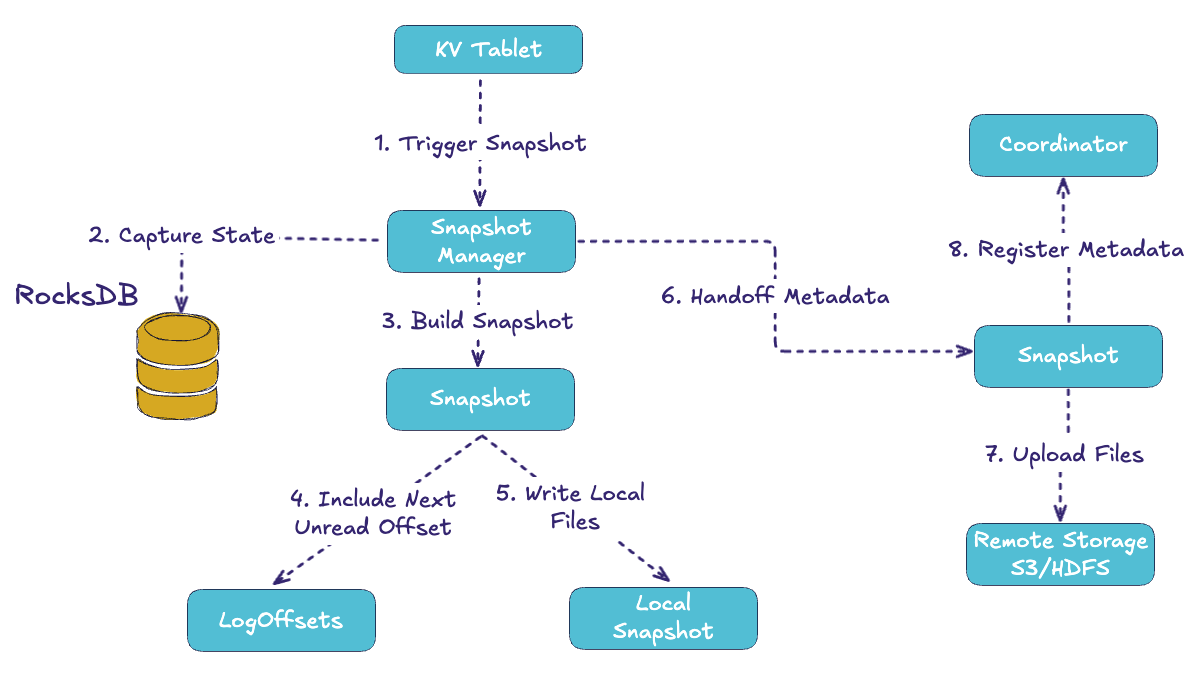

📸 The Snapshot Process

A running leader can’t rely only on logs. If logs grow forever, recovery would be extremely slow. That’s where snapshots come in. Periodically, the snapshot manager inside the tablet server captures a consistent checkpoint of RocksDB. It tags this snapshot with the next unread log offset, which is the exact point from which replay should resume later.

The snapshot is written locally, then handed off to the uploader, which sends the files to remote storage (S3, HDFS, etc.) and registers metadata in the Coordinator. Remote storage applies retention rules so only a handful of snapshots are kept.

This means there’s always a durable, recoverable copy of the state sitting in object storage, complete with the exact log position to continue from.

Snapshots make the system resilient. Instead of reprocessing an entire log, a recovering node can start from the latest snapshot and replay only the logs after the recorded offset. This reduces recovery time dramatically while ensuring correctness.

⚡ Failover and Recovery

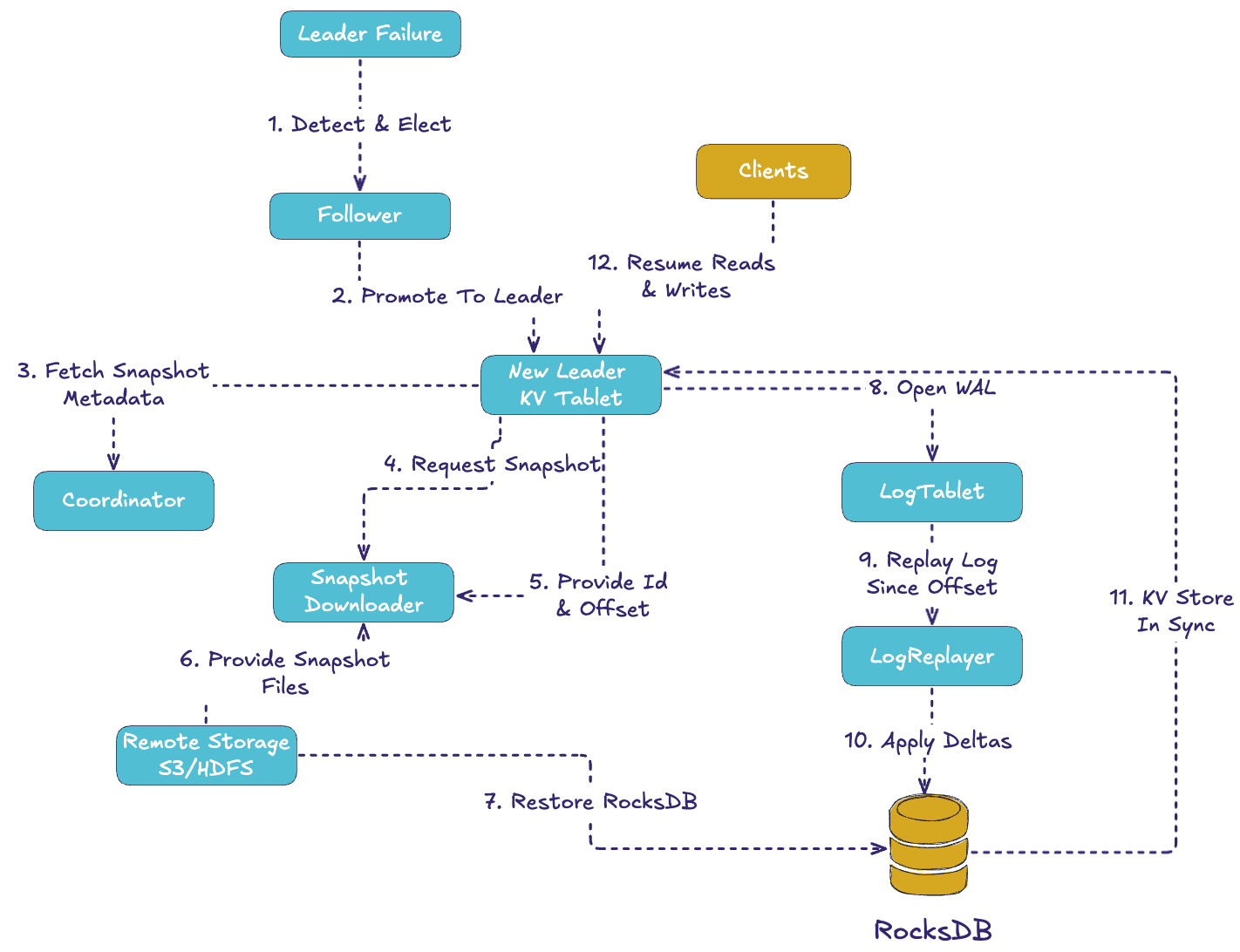

When a leader crashes, Fluss promotes a follower to leader. Followers are log-only today (no hot RocksDB), so the new leader must:

- Fetch snapshot metadata from the coordinator.

- Download the snapshot files from remote storage.

- Restore RocksDB from that snapshot.

- Replay log entries since the snapshot offset.

- Resume serving reads and writes once KV is in sync.

This process ensures determinism: the snapshot defines the starting state, and the log offset defines exactly where replay begins. Recovery may not be instantaneous, but it is safe, automated, and predictable. Work is underway to add hot-standby RocksDB replicas to make this even faster.

This process ensures determinism: the snapshot defines the starting state, and the log offset defines exactly where replay begins. Recovery may not be instantaneous, but it is safe, automated, and predictable. Work is underway to add hot-standby RocksDB replicas to make this even faster.

Note: For a large table, the recovery process might take even up to minutes, which might not be acceptable in many scenarios. To solve this issue, the Apache Fluss community will introduce a standby replica mechanism (see more here), so recovery can happen instantaneously.

✅ The Built-In Cache Advantage

What makes Fluss PK Tables really stand out is that the cache is not an external system. Because RocksDB sits right inside the TabletServer and is updated in lockstep with the WAL, you never have to worry about invalidation.

This means:

- No race conditions where the log is ahead of the cache.

- No cache stampedes on restart, because RocksDB is restored from snapshots deterministically.

- No operational overhead of scaling, securing, and reconciling an external cache cluster.

Instead of a patchwork of log & DB & cache, you just have Fluss. The log is your history, the KV is your current state, and the system guarantees they never drift apart.

By unifying the log and the cache into one design, Fluss solves problems that have plagued distributed systems for years. Developers no longer have to choose between correctness and performance, or spend weeks debugging mismatches between systems. Operators no longer need to run and tune two separate clusters.

For real-time analytics, AI/ML feature stores, or transactional streaming apps, the result is powerful: every update is both an event in a durable log and a fresh entry in a low-latency cache. Recovery is automated, consistency is guaranteed, and the architecture is simpler.

🔍 Queryable State, Done Right

Users of Apache Flink and Kafka Streams have long wanted to “just query the state.” There has been lot's of demand for this patterns.

Flink’s Queryable State feature tried to offer this, but it was always marked unstable, with no client-side stability guarantees and it has since been deprecated as of Flink 1.18 (and marked for removal), with project members citing a lack of maintainers as the reason.

Kafka Streams’ Interactive Queries are still available, but they require you to build and operate your own RPC layer (e.g., a REST service) to expose state across instances, and availability can dip during task migrations/rebalances unless you provision standby replicas or explicitly allow stale reads from standbys during rebalances. In practice, this adds operational work and consistency/availability trade-offs; under heavy concurrent reads/writes some teams have even hit RocksDB-level contention issues.

Fluss PK Tables deliver the same end-goal; direct, low-latency lookups of live state, but without those caveats: each write is durable in the log and applied consistently to RocksDB, and deterministic snapshots, along with log replay provide reliable recovery, so you can safely query state even after failures.

📊 Real-Time Dashboards - Without Extra Serving Layers

A recurring pattern in streaming architectures is to use Flink for the heavy lifting, like streaming joins, aggregations, and deduplication and then ship the results into a separate serving system purely for dashboards or APIs.

These external layers (often search like ElasticSearch or analytics engines) in lot's of cases they don't add analytical value; they exist mainly to provide a serving layer for applications and dashboards.

This introduces an important trade-off: every additional system means duplicate storage, increased latency, and extra operational overhead. Data has to be landed, indexed, and kept in sync, even though the stream processor has already computed the end state.

With Fluss Primary Key Tables, you don’t need that extra serving layer. Your stateful computations in Flink can materialize directly into PK Tables, which are durable, consistent, and queryable in real time. This lets you power dashboards or APIs straight from the tables, cutting out redundant clusters and reducing end-to-end latency.

In short: compute once in Flink, persist in Fluss, and serve directly, without duplicating storage or managing another system.

🚀 Closing Thoughts

The above are some examples use cases, we have seen recently and I'm only eager to see what users will build with Fluss - realtime features stores is another PK table use case currently under investigation.

Fluss Primary Key Tables are one of the most compelling features of the platform. They embody the stream-table duality in practice: every write is a log entry and a KV update; every recovery is a snapshot plus replay; every cache read is guaranteed to be consistent with the log.

The complexity of coordinating a log and a cache disappears. With Fluss, you don’t have to choose between speed and safety; you get both.

In short, Fluss turns the log into your cache, and the cache into your log, which can be a major simplification for anyone building real-time systems.

And before you go 😊 don’t forget to give Fluss 🌊 some ❤️ via ⭐ on GitHub